There are some big questions out there. Why are we here? What's life all about? Is there a god?

The answer to that last one is fairly obvious (No, of course there isn't. Grow up.), but as for the first two questions, I've been pondering whether the human race will ever figure it all out.

I guess non-specific questions of life, the universe and everything can be answered to some high degree of uncertainty by philosophers and genius-like sci-fi comedy writers, but I hope to look at it all from a scientific standpoint. ...Unfortunately, I seem to have mislaid own my personal standpoint (of the scientific variety) the last time I went time travelling, but I can pretty much recall the view from it.

At the cutting edge of physical science there are mysteries that have been left unanswered (although I know we have people working on them):

- In the field of classical mechanics, there's What causes gravity?

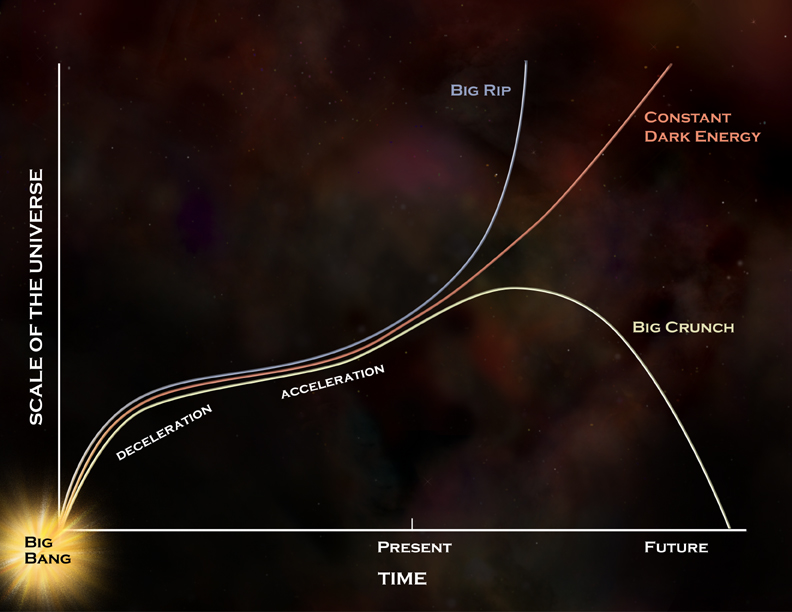

- In the field of astrophysics, there's What is the shape/size of the universe?

- In the field of quantum physics, there's the question Why does matter exist?

You may notice that these are all basically the same question. That question is How?

Or to be less succinct ... How did the universe form?

This is because all answers are easily revealed once you know the origin of the universe. Other big questions you may have thought of like How did life begin? can be answered with a simple sequence of 'cause and effect' that started when the universe began. Even little questions can be answered this way (although it isn't always necessary to go so far back): Can you explain Miley Cyrus' behaviour?... Well, first the universe came into existence...

Not only that, but I strongly suspect that if some genius (almost certainly not me*) is ever going to figure out the answer to just one of those big questions, then the answers to all the other questions will soon fall into place. And here's why (and how):

- The 'force' of gravity is caused by physical matter distorting space-time. All matter does this but no one knows how. They only know that it does, and that it distorts all space-time in the universe. I suspect the answer will be perfectly obvious once they've figured out how matter came into existence.

- Matter came into existence at the very beginning of the universe. We've currently got top men (and women) colliding particles under Switzerland to figure out what they're made of. In doing so, there may be some clue as to how they appeared from nothing. Which in effect is answering the question of how the universe came into existence.

- Once we have a scientific model for the origin of the universe, then we can figure out the shape of it, the size of it now, and where we are in it. At the moment we can only see a mere 13.7 billion light years away. We have no idea where the centre is, whether it's even viewable from where we are, or which way is up.

Personally, I believe in the omniverse theory. Sometimes. Ok, it really depends on which day of the week you ask me. But whether that's true or not, I believe the key to it all lies in matter. Specifically the nature of gravity/space-time.

You see, matter is this big mystery. It's stuff that the whole universe is made of, and it all sits in a 4 dimensional web of space-time (which incidentally, was also created at the birth of the universe). The two things are inextricably linked. Matter affects the whole universe and the whole universe is made of matter. They are one and the same. This is how matter came into being from nothing; it was all extrapolated from nothing, and the remnant of the 'nothing' that was left over, is the space-time continuum.

Therefore, to figure out the true nature of matter, is to figure out the true nature of everything.

But can it be done?

Science has come a very long way, in a very short space of time. I know that more hurdles will be overcome in the following decades which will give some clues to all this, as well as sparking new questions. However...

The answers are getting progressively difficult to obtain. Science is getting better still, but it's slowing down. I predict that if it's gonna happen at all, then the answers will start to flood in thick and fast, within the next 65 years. But after that, I don't think we'll ever figure it out.

Ask me in 30 years time, and I'll give you a more accurate prediction. But right now there's a 50/50 chance of us finding the answers in the next 65 years, though there's only a 10 percent chance of that.

* I'm so modest these days.